Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring (reconstructed 1913 version)

Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich

RCA, recorded 2014

Buy at Amazon.com

Esoterica for enthusiasts of the Rite

2013 and 2014 saw a cavalcade of new CDs commemorating the centenary of that most iconic masterpiece of modern music: The Rite of Spring. What distinguishes this particular offering from David Zinman and his Zurich-based collaborators is the unveiling of Stravinsky's original orchestration of the Rite. This is coupled with a performance of the Rite in its standard edition (finalized in 1967) and a half-hour long track with explanations and demonstrations of differences between the two (as well as various intervening versions and editions). The whole is bundled into a two-CD album with an attractive 110-page booklet with texts in German and English.

But first a clarification: despite the inaccurate labeling in the album booklet, repeated carelessly by some reviewers, the early version of the Rite recorded here is not what the audience heard at the work's premier on May 29, 1913. Instead, Zinman is presenting Stravinsky's unrevised autograph score, which dates from March 1913, and which was preserved in Basel by collector/conductor Paul Sacher. What Pierre Monteux conducted from at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was actually a second manuscript, copied from Stravinsky's autograph, that received numerous penciled-in revisions during the rehearsal process. This is confirmed in the liner notes, which state that the autograph "represents the status of the score before the corrections and alterations made in connection with the premier", and that "another manuscript [made by a copyist, not Stravinsky] was used as the master copy to conduct the premier". Since this latter manuscript, with its collected emendations, is the basis for the first published edition from 1921 and all the subsequent cheap editions available from the likes of Dover and IMSLP (often with various errors corrected), the Rite that is heard on most historical and LP-era recordings is actually closer to what was heard in 1913 than the "original" version recorded for the first time here. In recent years, the 1967 edition from Boosey & Hawkes has gradually displaced these various "Soviet" editions to become the standard basis for performances of the Rite. It gathers Stravinsky's collected errata from previous editions, and incorporates the 1943 version of the Sacrificial Dance, which is the only part of the piece that Stravinsky ever substantially revised later in life.

Though I'm disappointed at the sloppy labeling and lack of scholarly rigor in the accompanying notes (i.e., there's no comprehensive list of differences between the original and final versions), I'm glad to have this March 1913 version available as an insight into Stravinsky's thought process. Here are some of the most notable variances between the "original" Rite and the Rite that we know and love today:

- The last two notes of the final statement of the bassoon tune in the

Act 1 Introduction are a third lower than expected. Zinman thinks was a

pen slip, a case of missing ledger lines, and it clearly sounds wrong.

Incidentally, in all versions of the Rite this entire solo is pitched a

half-step lower than the otherwise identical solo that opens the piece

- In the Danse des Adolescents there are several audible

orchestrational differences. The famous string polychords at the

beginning originally lacked the all-downbow indication. At the dance's

climax, the folk-like main melody

was originally in the horns and violas instead of the more penetrating trumpets and soli cellos. Shortly after this climax a syncopated countermelody in the 4th horn is echoed in the low strings. In the final version that echo is given to two contrabassoons

- Speaking of the Danse des Adolescents, in the liner notes Zinman says that "at Figure 28 the score has 18 bars that were later struck out...we will certainly be playing them", but they're not heard here. Figure 28 (in every edition I've seen) comes at the aforementioned climax of the Danse, at the tutti where the E♭ clarinet enters with shrill mordents, four bars before the entrance of the above folk-like theme

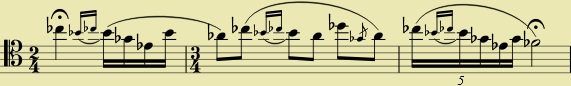

- The Rondes Printanières movement starts with a slow

primitive-sounding tune in the E♭ clarinet, doubled two octaves lower by

a bass clarinet. After the main section of this slow processional dance,

the E♭ clarinet tune recurs. But whereas in March 1913 the

instrumentation of the tune is the same in both places, in later

versions Stravinsky dropped the bass clarinet from the reprise and

replaced it with an alto flute (creating the unusual sonority of a

clarinet atop a much lower flute)

- An interesting detail in the Jeux des Cités Rivales is that in the two-piano version (which was completed in 1912 and is the earliest surviving version of the piece) a bass ostinato in the middle section moves up a whole tone six bars before it concludes, whereas in all the orchestral versions, including the one from March 1913, it stays at the same pitch level throughout. Presumably Stravinsky changed his mind on the matter between 1912 and 1913. After this passage comes a long orchestral pyramid that leads to the ending climax. In March 1913, a countermelody is played by muted (or stopped) horns whereas in the Rite that we all know it's played by open horns

- As noted above, the Sacrificial Dance is the only part of the

score that Stravinsky extensively revised after publication. His 1943

reworking of the Dance changes the notated metric unit from 16th notes

to eighth notes

and includes several subtle orchestrational changes. It was published in the US in 1945 by AMP, and is incorporated into the 1967 Boosey & Hawkes edition that Stravinsky considered to be "final and authoritative". This revision of the Dance was slow to be accepted by conductors, perhaps out of reluctance to pay for the more expensive American edition (whereas the various reissues of the 1921 "Soviet" edition weren't subject to normal copyright protection in the First World). Regardless, the original March 1913 version of the Dance sounds distinct from both the 1921 edition and the 1945/1967 editions. For one thing, there's no fermata over the rest following the first string chord.

And for another, several of the subsequent martelé string chords in this "A section" are plucked instead of bowed. The orchestration of the coda is likewise quite different (and more complex) in the March 1913 version. The tuba reinforcement of the minor thirds in the bass is missing (Zinman thinks Stravinsky's 1943 version was made with an eye to being easier for Stravinsky to conduct, and is written so that if the tubist and timpanist are in sync with each other, the ending conducts itself). The next-to-last bar has what sounds like a trill in the E♭ clarinet instead of the expected sul ponticello violin tremolos. And it sounds like there's a guiro accompanying the upbeat to the very last chord

Several of these textual differences are discussed by Zinman in the interview printed in the CD booklet and in the 35 minute track on CD 2 that I mentioned earlier. In this latter track, Zinman plays matching selections from the March 1913 and 1967 versions, and discusses various several other historical points of interest. This is the most intriguing part of the album really, and may be worth a standalone download in lieu of purchasing the entire set. Zinman has a personal connection to the Rite: he was Monteux's assistant and rehearsal conductor for several performances of the Rite in the 1960s, during which time he became acquainted with the work's textual history. The host of the interview asks his questions in German, but Zinman always responds in English so it's easy to for non-German speakers to follow. There's also a brief passage where a French-speaking bassoonist explains that French bassoons are narrower and made of a different type of wood than their German counterparts (which are used in most of the rest of the world nowadays). He suggests that Stravinsky might have had that specific instrument in mind when writing the groundbreaking opening solo (which starts on C5, considered outside the technical range of the instrument at the time). Two bassoonists subsequently play this solo on each type of instrument.

Another topic that Zinman covers in this lecture/demonstration is the Introduction to Act 2. This long, slow movement is the one part of the Rite that seems to drag on a bit. So I was interested to hear Zinman's speculation that Stravinsky originally intended it to be much shorter, but was obliged to lengthen it to accommodate an onstage scene change. Zinman also gives us, at the start of the track, a different novelty: a version of this Introduction with a five-bar concert ending appended. This was written by Stravinsky for Ernest Ansermet to use in a 1922 concert where there was not sufficient time to rehearse the rest of the second act. The liner notes devote a surprising amount of space to Ansermet owing to his nationality (and indeed it was Ansermet who first performed the Rite in Switzerland).

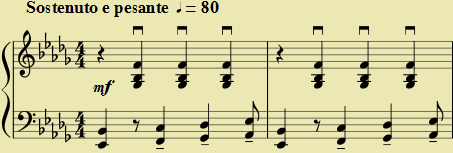

After all this promise, I'm sorry to say that the actual recordings of the Rite on these CDs aren't particularly good. As others have noted, the music just doesn't sound very clear and exciting, perhaps due to the acoustics in Zurich's Tonhalle or perhaps because of inadequacies in microphone placement and mixing. The wind instruments are distant and murky, and the recording lacks definition in the bass instruments, a flaw that's pretty deadly to the Rite (and to be fair, Stravinsky offers little help to the sound engineer with his propensity to subdivide cellos and double basses in a way that weakens their balance relative to the whole ensemble). Beyond the engineering issues, I quibble with Zinman's habit of sustaining notes that Stravinsky didn't explicitly mark as short, such as in the Évocation des Ancêtres when the bassoons echo the main theme. I grew up in Los Angeles, overlapping Stravinsky's residency there, and I studied and performed with some of the musicians that recorded his last works. They conveyed the expectation from Robert Craft and the Old Man that notes in his scores should be separated by default (i.e., if they're not slurred). Notes that were expressly marked staccato were to be played really short. But Zinman talks about how Monteux positioned the Rite in the tradition of Impressionist orchestral writing, in contrast with most conductors' vision of the piece as a radically new and rhythmically violent thing, so perhaps this way of thinking has informed Zinman's own approach to the score. There's a whiff of Debussy in several of the slow passages in these recordings. And on a conciliatory note, I'll say I was pleased by the Rondes Printanières movement, which many conductors belabor at a lugubrious tempo, but is taken at a crisper pace by Zinman, who delivers some welcome metric clarity (the bass instruments take the "and" of 2, 3 and 4 in the dance's 4/4 measures, making the downbeat uncomfortably ambiguous at a tempo slower than Stravinsky prescribes):

Clearly Zinman's insight on how the piece evolved in Stravinsky's mind and ears has guided how he approaches it in performance, and this perspective offers some redemption to a recording that's not otherwise of the caliber of the Rite's foremost advocates.

This album should not be your first, second or third recording of The Rite of Spring. But for those of us who love this work, it offers one of the closest glimpses you can get at just how the work progressed from Stravinsky's imagination to its materialization as possibly the single most important piece of music ever composed.

- Michael Schell

First published January 2016

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2016 by

Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.